It seems to me that Julian Barnes is one of those writers who manage to please all sort of readers, from those who regard themselves as demanding connoisseurs to those who get easily bored if they don’t get hooked by the plot, or the characters are too bland or too hateful. Maybe the key of such success is that Barnes gives you a bit of everything but never excessively (this being said under the assumption that nowadays readers are probably less patient than they were thirty or forty years ago, let alone in the nineteenth century). As far as I know most of his books are short, the characters are like many people you encounter in normal life, neither too evil nor too good, only normal human beings whose concerns, anxieties and hopes most people can understand; the plots flow smoothly enough so as to make you feel like if you were being carried by the waters of a river while at the same time enjoying the landscape, and all the while being fed spoon fools of “philosophy” but a bit watered down to get rid of any bitterness and not so often to avoid spoiling your enjoyment.

It seems to me that Julian Barnes is one of those writers who manage to please all sort of readers, from those who regard themselves as demanding connoisseurs to those who get easily bored if they don’t get hooked by the plot, or the characters are too bland or too hateful. Maybe the key of such success is that Barnes gives you a bit of everything but never excessively (this being said under the assumption that nowadays readers are probably less patient than they were thirty or forty years ago, let alone in the nineteenth century). As far as I know most of his books are short, the characters are like many people you encounter in normal life, neither too evil nor too good, only normal human beings whose concerns, anxieties and hopes most people can understand; the plots flow smoothly enough so as to make you feel like if you were being carried by the waters of a river while at the same time enjoying the landscape, and all the while being fed spoon fools of “philosophy” but a bit watered down to get rid of any bitterness and not so often to avoid spoiling your enjoyment.

I must say that, having read three of his books, I don’t quite count myself among his most ardent fans. The formula doesn’t work with me, or at least not completely: I see what is lacking; there is too much mildness; the “philosophy” is a snack rather than a proper meal, a number of witticisms, remarks and observations that, however suggestive, do not make up a whole discourse. It may be that, as often happens to me, I have missed the discourse altogether.

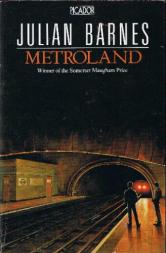

For such a short book, it took me a while to finish Metroland. Although, like the two protagonists of the book, I also believed myself a sort of intellectual when a teenager and rejoiced in aesthetical (rather than political) demonstrations against the establishment or the bourgeoisie or the people who took life too seriously or whatever, I didn’t really saw myself mirrored in those two kiddos whose knowledge and appreciation of French sixteenth century theatre and nineteen century poetry is, I must admit, admirable. Their little intellectual games and diversions are fun and quite clever and, if they have been invented by Barnes, I must say in all honesty that his imagination is quite impressive. This is probably what stunned me the most of this two lads and the world they built around them: their powerful imagination, their capacity to make the inherited culture products of the past their own and to use them in different ways, to shock, if not to destroy, the universe of self-deception which adulthood forces you to inhabit, often in spite of yourself.

But that is also the problem I observed in the book: after living the bohemian life in Paris (although really not doing much beyond losing his virginity), one of those two teenagers, the narrator and thus the one whose perspective the reader will logically tend to take for that of the writer (and this is again a problem with novels: who speaks on behalf of who?), enters placidly into that universe of grown-ups, settles down, gets married and finds a job intellectualish enough so as not to betray his principles altogether. He allows the gap that had already begun to separate him from his childhood’s best friend to widen until it gets to a point where they don’t speak the same language: our protagonist struggles but manages to dismiss those unwelcome thoughts that he might have done something grander with his life, whereas his friend, still keen on becoming a true poet, seems to be losing an imaginary war on behalf of the no less imaginary values that art is supposed to embody. He has published a book of poems but no one reads him; no one really heeds him.

So what is Barnes trying to tell us, if anything? I am not sure, really. Maybe that an ordinary life is not necessarily devoid of the pleasures of intellectual activity and, even more, that when such dedication to intellectual pursuits becomes a pose it loses its raison d’être; or maybe that it is precisely in ordinary life that the facts and events and realities and materials that make up genuine philosophy are to be found. This may strike more than one reader as a bit too complacent, and it may be argued that to think out of the box you must leave its confortable insides and get wet under the rain. Barnes is an observer of the facts of life, and he’s got a sharp eye, which is good, but he is too careful not to touch the object under the microscope. The pattern is very similar, as far as I remember, in A Sense of an Ending (apart from the ending itself, quite open to interpretation in my opinion) and in Staring at the Sun: people living normal lives and making certainly interesting discoveries about the complexities of normal lives. Maybe that is the reason why most readers (in the end subject to “normal” lives most of them) seem to enjoy his books. But we also need abnormal lives, we need writers more willing to stir the object under analysis and to trigger a reaction, to explore beyond what happens and open a door into what may happen. Maybe I need them because my life is way too normal.