I must st art this review, I do in fact feel obliged to start this review, by mentioning that a certain person whose avatar’s name is Krista, admitted in a review published in Goodreads back in 2008 that, although she did not enjoy Les Mots (The Words in English) as much as a smarter person might have done, the book caused in her a deep impression nonetheless, because she could not help but fearing that her little child, an avid reader like Sartre, will, and I am now quoting her “have an insane interior life like Sartre did. And a wall-eye (sic.).” She says that she is not very smart; well, I think that she is a genius. Bad reviews are always, always, the most amusing to read and often the most revealing. I love them (such a shame that I am a nice guy).

art this review, I do in fact feel obliged to start this review, by mentioning that a certain person whose avatar’s name is Krista, admitted in a review published in Goodreads back in 2008 that, although she did not enjoy Les Mots (The Words in English) as much as a smarter person might have done, the book caused in her a deep impression nonetheless, because she could not help but fearing that her little child, an avid reader like Sartre, will, and I am now quoting her “have an insane interior life like Sartre did. And a wall-eye (sic.).” She says that she is not very smart; well, I think that she is a genius. Bad reviews are always, always, the most amusing to read and often the most revealing. I love them (such a shame that I am a nice guy).

Certainly, my little ones, Sartre (nicknamed the “arch-whiner” by some other hilarious reviewer) was from the most tender years of his infancy, a bookworm. You know what I am talking about, the typical kid who hasn’t got many friends and no one really wants to play with him in the park because he is weak and feeble and even a bit girlish, and of course he grows up being aware that the other kids are stronger and more athletic, which in turn pushes him to seek refuge in other people’s lives, in books that stimulate his imagination and in the comfort of an imaginary world where real life is not so likely to hurt him. You know, in short, the typical infancy of a future literary success, only that those who spent their infancy locked in their rooms, surrounded by books and afraid of facing real life but, unlike Sartre, did not get to see any of their works published and died unknown, had the same infancy but, unlike the myth would have it, did not get anywhere. Sartre, the myth, is one, the other unhappy children, are thousands.

To be honest, the book is not only about Sartre’s unhappy childhood. Actually, although apparently at some point he is supposed to state that he hates his childhood (I don’t remember reading such a thing) the impression you get is that he was happy among his paper friends and that he somehow knew that literature and the world of knowledge and human experience transmitted through the written word was the world in which he had been chosen to dwell for the rest of this life (yes, he seems to believe that he was chosen rather than he chose it). Ten years old Sartre already knew that he was destined to become a writer, that no other interest or event would deviate him from this path to intellectualness. Obviously, he does not depict himself as little prodigy undeniably heading towards literary stardom; doubts assaulted him as they may and often he seems to be making an effort to belittle his incipient intellectual abilities, perhaps following a natural impulse to avoid showing off too much. He even admits that in a couple of occasions he played the smart kid before his relatives and teachers only to get in return for his pretended cleverness a reprimand with a humbling message: literature is superfluous when it is not honest.

The fears that would supposedly breed Sartre’s thinking (and I say supposedly because he does not openly link his infancy with his future intellectual tribulations), are there already, harassing the poor boy and not letting him sleep well but also shaping him and preparing him to embrace future ideas and ideologies (Marxism, maybe). Death and God are two of the most annoying fellows he had to deal with in those days; Love, the third member of this trilogy of well-known bullies, doesn’t seem to have bothered him much in those days (we all know, however, that he was meant to become an open-minded lover). God and Sartre were playmates (and here, please, don’t heed your nasty minds, even though the very idea is quite comical). Sartre would listen to God and they got on well, but then he started to grow up and could not bear His demands of admiration, and it got to a point where he could simply not care about Him anymore. Yes, Sartre still wants to be friends with God and would like to go for a drink together and chat about the old good times, but often He is nowhere to be seen and he ends up forgetting Him.

Death is altogether a different matter. She is always there, she is persistent, and her presence is very physical. Let’s not forget anyway that Death is the one that will take us away but also the one under whose power is to decide at what point the narrative we are will come to an end and the final judgement on our deeds will begin. And I am not talking about our moral behaviour, but about the character, the idea about us that is left behind when the real human being, less superfluous than an idea or a character, does not exist anymore. Little Sartre was mostly concerned about this second aspect of Death’s undertakings. Knowing as he knew that he was bound to spend his life writing, he brooded about the idea of dead-Sartre-the-literate when he was still living-Sartre-the-bookworm-kid. He acknowledges daydreaming about being the author of an unpublished book, which is all of a sudden discovered by some publisher and becomes an object of praise and admiration, while the whereabouts of that mysterious Sartre who wrote it remain unknown. In a sort of funny episode of that fantasy he overhears in some café a woman confessing to her friends that she would love to marry that Sartre who has written such a marvellous book. He gives her a sad smile and goes away, exactly what Death in the most romantic of her moods would have suggested.

Apart from intellectual amusements, there is the real stuff behind: nostalgia. Sartre is not so full of himself so as to forget completely that he is supposed to be writing about a boy and not about a fifty something years old philosopher remembering how words made him what he is, even though this is the purpose of the book. Not that Sartre acknowledges nostalgia as an element to take into account, but it sneaks in through the choppy portraits Sartre makes of his grandparents and his mother, as well as in the excitement he recalls feeling when mum would take him to the banks of the Seine to buy books, or to the cinema, or to the Luxemburg Gardens. Nostalgia is present in the accounts he makes of the books of adventures he loved so much, in the memories of evenings spent in his room entranced by the charm of a story, in the dim light of the library, in the smells, the habits and the small games he used to plays with those adults that the reader may take for granted that died long ago.

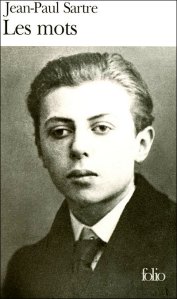

I guess that there is something of that little Sartre in all of us who discovered, still in our infancy, that reading could be exciting and fun; all of us had also our “philosophical concerns”, and possibly all can recall staring at a shelve full of books at home or at a book shop, trying to have a glimpse of the worlds hidden in those books by reading the title and looking at the pictures in the cover. That feeling of “amazement”, to put it somehow, is at its purest when the World is still new and fresh and living has not turn it into a fractal, a repetition of experiences and feeling that wears out somehow its appeal and enchantment. Possibly all of us can recall discovering aspects of about life that we did not like, that frightened or saddened us, and some of us have ever since been looking for a solution to those unhappy discoveries. I am pretty sure that the memory that will linger in my mind of Les Mots is that feeling revisited of the first approach to the mysteries concealed by literature, only to be revealed to those patient enough, or maybe curious enough, to submerge themselves into the pages of a book. This feeling cannot be detached from the sensations that render it real. All this said, I don’t want to forget one last thing: unlike what I expected, only two photos of Sartre came up when I entered “ugly philosphers” in Google Images, and none of Habermas… strange, isn’t it?