I have b een lazy as hell these past days; well, lazy and also practising my French, but I must say that unfortunately I refer to the language. I am not sure to what extent this joke relies on a cultural reference to be missed by those who don’t speak Spanish, but, anyway, it is sexual and consequently it is funny even if you don’t get it. This in turn begs the question of whether anyone who speaks Spanish does actually read my blog: if anyone does, I will politely ask him or her to leave a comment rating my joke, which in turn begs the question of whether a joke can be rated by measuring its quality on a numeric scale and, since I am asking so many questions, I can beautifully divert the whole thing, the pretext having been found, towards a domain born to question, namely, the nouvel roman, that is, the French literary movement within which this novel and its perpetrator must be ranked, thus bringing literary and humoristic ranks together for once and for ever.

een lazy as hell these past days; well, lazy and also practising my French, but I must say that unfortunately I refer to the language. I am not sure to what extent this joke relies on a cultural reference to be missed by those who don’t speak Spanish, but, anyway, it is sexual and consequently it is funny even if you don’t get it. This in turn begs the question of whether anyone who speaks Spanish does actually read my blog: if anyone does, I will politely ask him or her to leave a comment rating my joke, which in turn begs the question of whether a joke can be rated by measuring its quality on a numeric scale and, since I am asking so many questions, I can beautifully divert the whole thing, the pretext having been found, towards a domain born to question, namely, the nouvel roman, that is, the French literary movement within which this novel and its perpetrator must be ranked, thus bringing literary and humoristic ranks together for once and for ever.

Even though the irony of it is quite cheap, let me address this matter of questions and literature with a question: why saying “questioning domain” when speaking about the nouvel roman? Because like pretty much all artistic movements in the 20th century the raison d’être of this new way of approaching the art of writing aimed at questioning the validity of the methods used during the 19th century in terms of the artistic representation of the world, this being, furthermore, a characteristic of the 20th century itself, I mean, to question everything, to doubt of everything and, if necessary, to destroy rather than to construct. The sharp, well defined and easily recognisable forms of the 19th century’s imaginary worlds give way to the blurred, distorted and subjective worlds of the 20th century; imaginary worlds as well, but much more aware of their fictional condition and for that matter much more fragile and insecure.

Thus, the nouvel roman wants to get rid of the preconceived plot and the ready-made characters that, like a dictator, govern with an iron hand the 19th century novel. Also, if on the bargain it can at least reshape space and time that would be quite convenient, because the 1950s where simply too complex and at the same time too ephemeral to be contained within those old-fashioned conventions called objective space and linear time. As already pointed out, the great enemy to be defeated was the 19th century novel: to be more exact, not the novels written in the 19th century, whose brilliancy and suitability for their times no one would even dare to question, but the tendency of the novel itself, as a cultural artefact, to mimic their methodology.

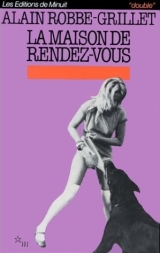

The consequence of this sort of intellectual approach to the idea of a novel that may verily account for our modern times is a work like La maison de rendez-vous. I am not going to bother you with the plot, for two very simple reasons, the second of which is barely debatable: first of all, because that is never the point of my reviews and, secondly, because there is no such a thing as a plot in this novel. Don’t believe me? Read the book and tell me what the hell it is about. Of course, you can roughly describe things happening and themes and put them together and there you have a sort of plot, but this will be doing little justice to what I suppose were Robbe-Grillet intentions.

The world of this book is not subjugated by the linear constrains that govern the traditional novel; events that had supposedly provoked other events are in turn provoked by the events they initially provoked (yes, it makes sense), the character’s identities are by no means well defined other than by a few constant features, the identity of the narrator is utterly unknown to the extent that if shifts, in the middle of a paragraph, from the apparently omnipresent narrator often mistaken with the writer himself, to the character whose actions have been described until that moment.

In short, it is a fluid world but not one, conversely, driven by chance, because it is the reader the only one who does not seem to be at ease in this game. The characters, on their side, do not detect this particular state of things; it seems that for them everything unfolds in accordance to the most sensible logic. But, then again, they are not the rendering of the common human being, and neither does the time that rules over them behave in the way it does in our ordinary lives: one of the most outstanding aspects of the style of the narrative is that Robbe-Grillet freezes some apparently trivial scenes, which will occur several times and will thus be described again, always in a suggestive manner which manages to imprint some sort of aesthetic beauty in the anecdotal.

But this world works because it is made of words. I mean by this that, in spite of my admiring the book and, above all, having honestly found in it a very genuine form of aesthetic pleasure, the doubt still remains of whether this small and uncanny universe, for all its references to very human themes like sex, drugs, sodomy and murder, is strong enough to stand on its two legs if confronted with the iron certitude and substantiality of an universe designed in the fashion of the traditional novel. To address this matter from a different perspective, I think that it is perfectly admissible to inquire whether the aesthetic alternatives emerged as a clear response to and thus as an opposition to old paradigms are as strong as those defied paradigms.

The nouvel roman may be a very sophisticated product whose aim is, of course, not only and probably not even to defeat the traditional novel, but rather to redo it in order to render it more adjusted to the changing sensibilities and perceptions of reality of a given period. This is definitely worth doing and, I must say again, it can give birth to fine books like La maison de rendez-vous. But the reality is that, whereas so many 20th century movements have lived intensely but died young, the old 19th century ways stay alive, which I believe to be even more the case when it comes to literature: Balzac and Zola, the guys against whom Robbe-Grillet stands, keep being read and being imitated by the thousands; the nouvel roman is, I fear, a rarity only appreciated by a few. And, in keeping with a point of view already held in another review, maybe it is not the mass audience that is to be blamed; maybe, the 19th century novel still appeals to many readers and tells them more about their world than other experiments, however well executed and suggestive they may be.

I know that the “fascist critic”, may his soul rest in peace, would have scorned me for being so feeble and admitting that maybe the average reader is entitled to his or her taste and prefer a contemporary pastiche to a proper intellectual effort. What can I do, I am a socialist. I believe, though, that literature is not an entertainment and that its greatness lies in being an alternative to academic disciplines in the way we approach reality and make sense of it. Literature must be an intellectual activity, an exploration, an enquiry over the nature of the world we leave in and the way we perceive and construct it. Otherwise, its very existence would be meaningless. Of course, one thing is to condemn a moral system and a completely different task is to build a new one from scratch. Anyway, no one is going to look down on Nietzsche for his failure. Likewise, let me pay homage Robbe-Grillet in this my humble blog, I will not raise my voice against you, my friend, because you have also waged your own war and, alas, you may have not come out victorious, but you fought many a beautiful battle.